Women's History Month: Mary Phelps Jacobs, entreprenuer and no stranger to scandal

27th Mar 2019

“Well-behaved women seldom make history”- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

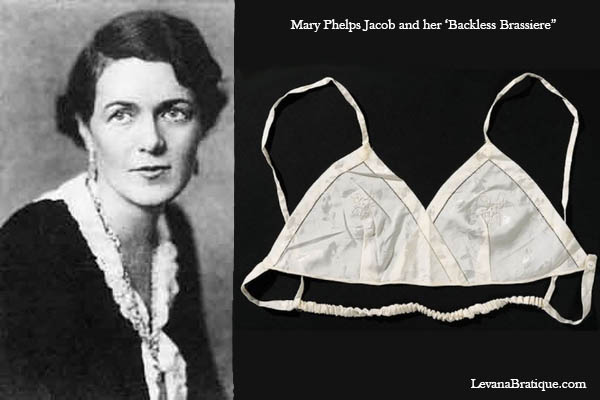

As we close out Women’s History Month, we wanted to delve just a bit deeper into the life of Mary Phelps Jacobs, the woman credited with patenting the first bra.

Born in 1891 in New York, ‘Polly’, as she nicknamed herself, grew up living an upper class lifestyle. In 1910 at age 19, she was preparing to attend a debutante ball. The undergarment style at the time was still a stiff whalebone corset, which was tight, uncomfortable, restrictive, and "jammed her large breasts together into a single monobosom." The corset poked out of the plunging neckline of her sheer evening gown, so on a whim, Polly fashioned two of her pocket handkerchiefs and some pink ribbon into a simple bra. Her new undergarment complemented the less restrictive fashions of the time, and friends and family were soon asking her to create some for them, too. Word spread, and when a stranger wrote offering her a dollar for one of her creations, she realized she was on to something.

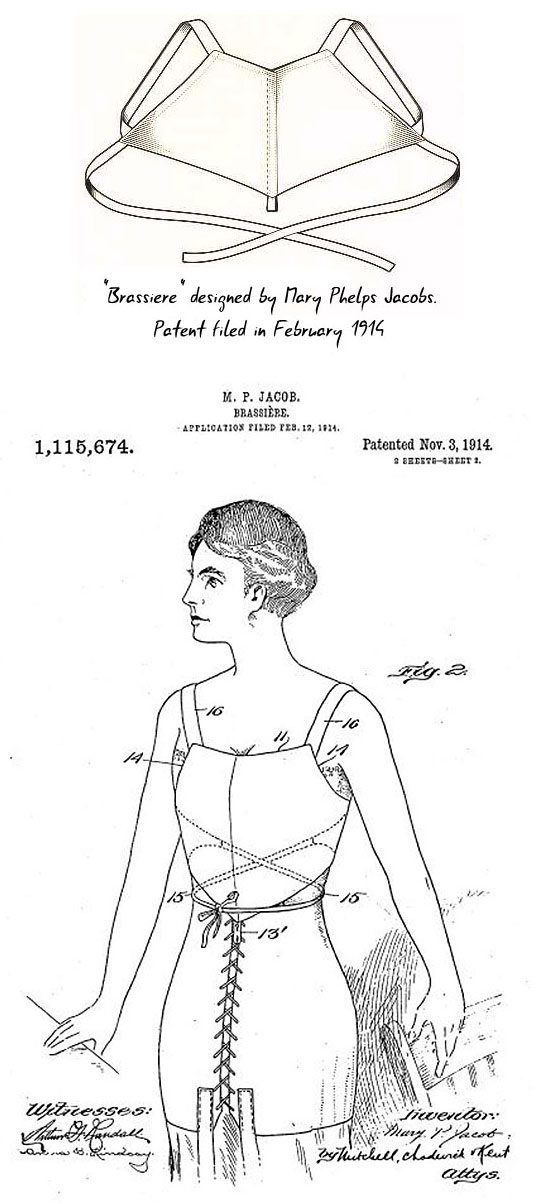

Polly began the process of copyrighting her design, writing to the U.S. Patent Office that her Backless Brassiere was

"capable of universal fit to such an extent that...the size and shape of a single garment will be suitable for a considerable variety of different customers" and was "so efficient that it may be worn even by persons engaged in violent exercise like tennis." In 1914, around the same time she married childhood friend Richard Peabody, the patent office approved her request, making Polly the first to patent a bra in the United States.

The lack of metal in her timely invention made it a perfect alternative during World War I, when corset construction was prohibited to conserve metal for use in building battleships. Polly started the Fashion Form Brassiere Company in Boston, where she employed two women to manufacture wireless bras. She received a few orders from department stores, but her business never really took off. Polly’s lightweight, soft design didn’t force the breasts together like the corset had, but also didn’t offer much support.

Her marriage to Richard was also failing at this time. They had two children together, but her husband had come home from the war drinking heavily, and with the curious fascination of watching buildings burn. In 1920, Polly attended a picnic and met a passionate, (also) hard-drinking WWI vet named Harry Crosby. He aggressively pursued her, and they quickly began a relationship that scandalized New York and Boston society at the time. Polly later described Harry's character as: "He seemed to be more expression and mood, than man, yet he was the most vivid personality I've ever known, electric with rebellion.”

In 1922, Polly divorced Peabody and married Harry Crosby. Crosby relied on a generous trust fund, so he discouraged her from working and convinced her to close her business. She sold her backless brassiere patent to the Warner Brothers Corset Company for $1,500. (Warner’s then went on to make over $15 million dollars from the patent over the next 30 years. I wonder if that ever came up in conversation between them?)

This headstrong entrepreneur wasn't done making her mark on the world quite yet; she maintained a fearless drive that served her through world travels, questionable taste in men, heartbreak, scandal, and many exploits.

After marrying Crosby, they moved to France, and at her husbands request she took a new name: Caresse Crosby. Harry had a penchant for living in the moment, and women, and their marriage was marked by many affairs (first only by Harry, and eventually Caresse followed suit).

In 1927, she founded a publishing company, first called Éditions Narcisse (and later Black Sun Press). She was instrumental in publishing some of the early works of important authors including Kay Boyle, Ernest Hemingway, D. H. Lawrence, T. S. Eliot, and Ezra Pound.

Harry shot and killed himself and one of his mistresses in 1929, an event that made headlines from New York to London, and spurred much gossip and speculation. Caresse got through it by focusing deeply into her work, establishing Crosby Continental Editions, which printed works by Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, and Dorothy Parker.

In the mid-1930s, a forty-something Caresse left Europe and returned to America. In that time, she had a relationship with black actor-boxer Canada Lee (at a time when interracial relationships were still illegal), opened an art gallery in Washington D.C., founded the art and literary magazine Portfolio, and had a three-year marriage to football player and alcoholic (sensing a theme here) Selbert Young, who was 18 years younger than her and “was always asking Caresse for money, he crashed her car, he ran up the telephone bill, and he used all her credit at the local liquor store.” She maintained a lively social life with many friends in the art and literary community, including Spanish painter Salvador Dali and his wife Gala, and author Henry Miller.

By the 1950s Caresse had purchased a castle in Italy to support an artist community. She also became politically active, founding two organizations that aimed toward pro-peace movements and campaigning for prisoners of war: Women Against War and Citizens of the World. When she died in Italy at age 78, her TIME magazine eulogy focused on her contributions to the written word, calling Caresse the "literary godmother to the 'lost generation' of expatriate writers in Paris.”

Whew! What a life! But seriously, at some point shouldn't her friends have sat her down and been like, "Girl, we need to talk about your choice in men..."?